Robots, Rockets, and Innovators: The Advantages of Intelligent Failure

Listen to this article in 7:33. Voice generated via AI.

I'm in Huntsville, Alabama, on day three of my son’s robotics competition for high school students. The city is buzzing with young engineers, some dressed in Star Wars costumes, others with matching green striped ties knotted around their foreheads. It’s a beautiful celebration of nerdiness.

In each match of the competition, run by First Robotics, three teams’ robots compete against three others. To earn points, the robots must pick up objects and shoot them like frisbees or basketballs into targets. Each match lasts three minutes and 15 seconds, with the robots running autonomously according to algorithms programmed by the teams for the first 15 seconds.

This is my son’s third regional competition this year. His team earned second place in the first two, and they’re hoping first place will be theirs this time. With each successive competition, we’ve started to see the top 20% of higher-performing teams pull away from the rest of the pack.

In that divide lies a lesson that can be applied to your business. It’s certainly shifting the way I am thinking about our organization and a new book that I’m working on with Verne Harnish about the strategies mid-market companies use to scale.

Intelligent Failure: A Strategy for Growth

The difference I noticed between the top 20% and the rest of the pack is that the best teams have been learning with every collision in every competitive arena. They didn’t design the perfect robot for the first match. They didn’t figure out the wheels that would propel it, the arms that would pick up objects, and the shooter that would fling those objects all at once.

In the first competition, some of those parts worked well and some were still immature. But the teams put their robots out into the arena, and in the clash of competition under the lights, music, and roaring crowds, they learned what did not work. They did this, not in the sterile conditions of their workshops, but out there in the real world.

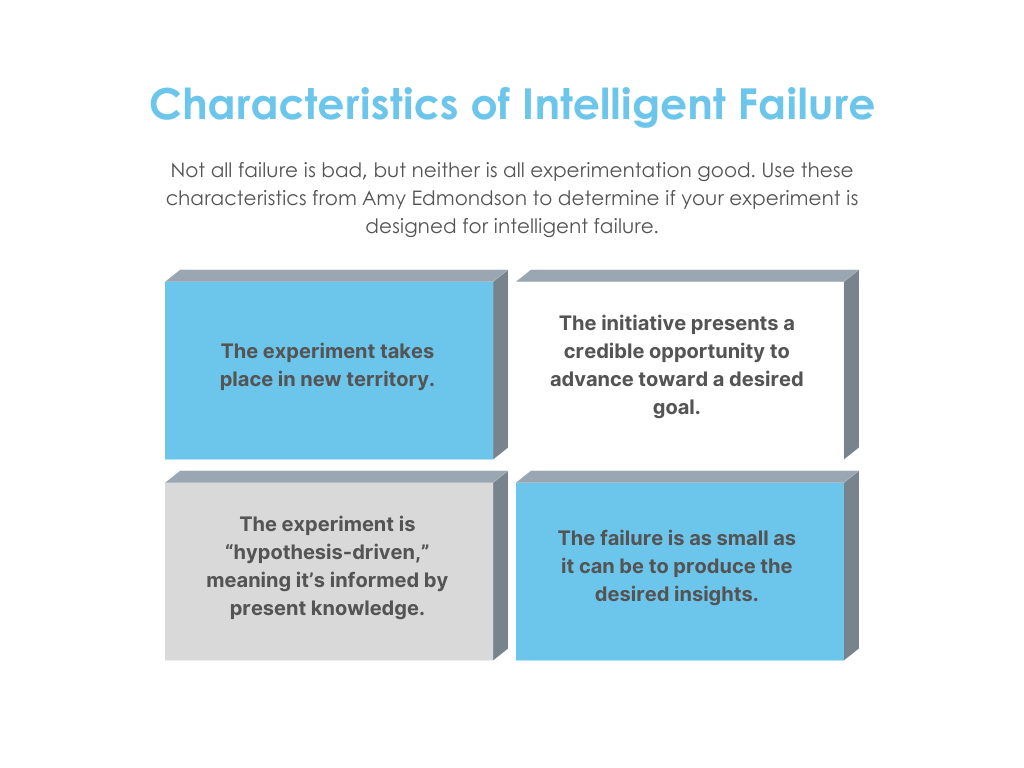

They failed, but they learned. Author and Harvard Business School Professor Amy Edmonson knows what I’m talking about. I interviewed her this week covering her latest book, Right Kind of Wrong: The Science of Failing Well. She laid it out for me. All experimentation is not good, but neither is all failure bad. The biggest mistake people make in experimenting stems from not being able to recognize when to take an intelligent risk that could expose yourself to a potential intelligent failure.

Experimentation and Continuous Improvement

At the robotics competition, the students, at least the ones on the high-performing teams, get it. Sometimes they take risks. They try to design an arm for a robot, and they don’t know if it’s going to work, but they build it, compete with it, and then they evolve it or they drop it. And they don’t invent it all from scratch. They look at what has already been done that works.

In the robot pit, inside the convention center with three-story-high ceilings, you will find the booths, one for each team, emblazoned with that team’s name, and filled with their tools. Whenever the robot is not in competition, the team is working on it. Five to 10 teammates huddle around the machine, pointing, discussing, and adjusting.

Around those booths, you will often see players from other teams. They hover around taking photos and videos, peeking into how other teams have solved mechanical problems that their team needs solutions to. They are learning from each other, and their learning is amplified by the 50 to 100 other teams there.

Intelligent Failure Defined

Amy defines intelligent failure by these characteristics:

The experiment takes place in new territory.

The initiative presents a credible opportunity to advance toward a desired goal.

The experiment is “hypothesis-driven,” meaning it’s informed by present knowledge.

The failure is as small as it can be to produce the desired insights.

Embracing Intelligent Failure in Entrepreneurship

As Verne and I are preparing to write our upcoming book, I’ve noticed that the great entrepreneurial stories I’m studying also fit this pattern. Our society likes to simplify the success of entrepreneurial ventures, like telling the story of one idea: Michael Dell selling computers directly to consumers or Sam Walton building stores in rural areas.

Business schools still teach people to write business plans. The implication is that budding entrepreneurs need to figure out who their customer is, what their product is, how to price it, what the distribution model will be, how to organize operations, how to staff the organization, and what the mission is. We are encouraged to figure all that out before getting into the arena.

An “Anti-fragile” Approach to Innovation

But here I am just outside Rocket City, Alabama, where Blue Origin and companies working for NASA are building rockets and launching them. I’ve worked with several clients in the industry of missiles, rockets, and space. There is a strong drive for perfection. Of course, if you get a product like that wrong, terrible things can happen. A failed launch is an embarrassment.

But Elon Musk’s SpaceX took a different philosophy. They tried to make sure every launch was successful, but they celebrated even when the rocket fell back to earth, because they learned, and because they were pursuing intelligent failure, which means pursuing something someone else has not yet figured out. They built an advantage of knowledge and experience. They separated themselves one step further from the competition.

It’s almost as if the great robotics teams and the great rocket companies here are “anti-fragile.” They get stronger through the failures, through the clashes in the arena.

Launching into the Marketplace with Confidence

So, let’s learn from these robot and future rocket builders. Let’s not wait until we have the perfect design. Let’s not make it all up from scratch, but let’s make smart failures. Let’s get our “robots” into the arena, into the marketplace, in front of customers, in the line of competition, even before we know they’re ready.